Clearly the next step in doing a George Plimpton-style excursion into the wacky world of phonetic alphabets was to try and design my own so I too can join the exclusive club of people creating scripts that nobody cares about or uses regularly. As it's been a while since the first parts of this series, check out parts 1 and 1 1/2 of Phonetic Phun so you can get caught up on what I'll be talking about and which scripts I'm referencing. In my reviews of the most notable phonetic alphabets for English some design principles made their case, guidelines that could assist in crafting a fine artificial script:

1.) Easy to write

2.) Internal logic

3.) Internal distinctiveness

Hopefully these rules are simple but comprehensive, making sure that you don't have something that's simultaneously confusing and difficult to write, such as Barton or Ewellic. The elegance of Shavian was too tempting to ignore, obviously, so I'd need to keep some of the internal logic, such as having sounds that are clearly related, such as "ch" and "j", have similar shapes, and the fact that nearly every character can be written with a single stroke is also too excellent to ignore. However, I wanted to avoid some of the confusion with Shavian due to its simplicity. The "best in show" script for one that was less simple and less easy to write was Deseret, with its old-world, blocky personality, but that wasn't without its problems, such as a higher risk of carpal tunnel syndrome. With all of these things in mind, here's what I came up with:

Yes, I know this is initial draft is all a bit much to look at at first, but hear me out. My strategy was to take visual inspiration from the shape the mouth makes when forming each syllable, stylizing the shape as seen from a right-side profile and cross-sectioned to see just the front teeth, lips, roof and floor of the mouth and the tongue. For example, "t" and "d" are formed by placing the tip of the tongue at the intersection of the upper front teeth and the roof of the mouth, and so the basic shape is a diagonal line meeting a straight one above it on the right side, making a 45 degree angle. To differentiate the letters the "d" moves the lower line to meet the center of the upper line - this way neither one is too difficult to write and with practice it can be easily differentiated. Likewise "f" and "v" are formed by placing the lower lip close to the upper teeth to create a small aperture, and I had sensed that my lower lip was placed a bit higher for "v" than "f", so therefore the intersection of the two component lines was placed higher. Other visual relations included "n" and "m": "n" is formed much like "t" but because the sound was stopped rather than exploded I put a line dropping down from the diagonal to create a wall, and the "m" was that with an added tail at the bottom, like a cedille, to visually relate to how the lips close to create the "m" sound. In each case a miniscule and majuscule was created - those lines through each letter represent the height relationship between each letter, so the majuscule letters extend above the miniscule ones. There are a few graphemes that are similar to their Latin counterparts, such as the short "i" sound, and ones that are similar to different sounds in Latin, such as "u" which is identical to Latin's "o", but I kept true to my process and those symbols made the most sense to me both logically and aesthetically. I wanted to keep majuscule and miniscule rather than do away with it like Shavian and Ewellic as a nod to how European languages write with clear beginnings to sentences and also to preserve the official status of names and titles. I made a number of ligature characters not only for very common letter combinations, such as "st" and "sd", but also for all the basic articles and pronouns, as well as "and". I kept another element from Shavian in making ligature characters for each vowel ending in an "r" sound as those combinations are so liquid as to appear as one syllable and they are fairly common in English. I also couldn't resist borrowing an element of Deseret, namely the rule that you can use one character for "the", and in both Deseret and my alphabet it's the thick "th" character (as in "the").

I believe the most important new inclusions, however, are two letter combinations that are very common in modern English but are conspicuously missing from all the alphabets I covered for these articles: the "x" and "qu" sounds. I can understand their disqualification from the others on the basis that, not only can a case be made for their being two syllables rather than one ("ks" and "kw"), but they are imported from Latin-based languages and aren't true to the spirit of English's Germanic roots. The latter argument is a bit hard to swallow these days, considering the Norman invasion was a thousand years ago and we've been using these sounds ever since then with no problem, but the first one merits discussion. Yes, these sounds are both combination sounds, but I have a number of ligatures already made and there's no reason not to make two more if the price is right. For "qu" I made a ligature of "k" and "w" with "w" on the left, making a kind of speech bubble character, and for "x" I created a new character entirely. With both miniscule and majuscule forms as well as ligatures the alphabet contains over 100 characters, far more than any of the other scripts, but in doing this almost every syllable and fundamental combination in written English should be covered with a single grapheme. I ended up calling the script (for now) Anampha, after "ANglo-AMerican alPHAbet", as I'm under no illusions that it would work for any other language; in the legend you can see its representation in the alphabet. In keeping things simple and easy to write a few of the characters ended up looking similar, but in testing I was able to keep them all straight with some practice. Here's a longish example, using Tom Wilkinson's big monologue at the beginning of Michael Clayton:

Obviously some small revisions were done to the original alphabet during and after this, such as removing the bottom line of "o" and the bottom connector of "p", things that made writing those letters unnecessarily irritating, but somethings I was very pleased with, especially the "ur" symbol, a sound that shows up a LOT in English. I also quite like the capital "ai" symbol for both the letter and article, giving a prominence and grace to the beginnings of a number of statements in this example. One problem that I still haven't worked out is how to represent hyphens, as "ee" is represented with an identical symbol in my alphabet. As the symbol is now, a hyphen with an angular dip in it, it's difficult to write accurately and ended up looking like a mistake most of the time. There are a few symbols which are still easy to confuse especially if hand-written, such as "ei" which is plainly an "ai" that got sat on - that grapheme is still tricky to write even after having written a substantial amount of material in the Anampha. As you can see my own handwriting standards got the better of me occasionally, such as the drunken sense of line and letter spacing that ended up confusing me when reading these passages after the fact - these issues didn't exactly clear up after more writing, though as my assurance with the characters improved the spacing did start to resemble the words I was trying to write. I managed to get out a particularly long passage, an entire short story by Lord Dunsany, a legend in the world of fantasy literature, called "The Hurricane". "The Hurricane" is actually one of my favorite stories, the witnessing of a Hurricane speaking with an Earthquake, and you can see the full text here. This is what it looks like in Anampha:

I'll leave that last line untranslated for those who like codes and Lovecraft references. This was written before a couple final touches were made to the script but in essence it shows everything I was going for with Anampha: elegance, distinction and ease of writing, all cutting down the number of characters needed by roughly a third and clearing up inconsistencies. In my excitement I came up with another idea, this one a bit more florid than the last:

These cast-off bits of wrought iron are the "ceremonial" version of Anampha. If used in a more fantastical setting than the real world, such as a fantasy novel, the story's interior world could use a script exclusively for religious texts or government announcements, hence the "ceremonial" designator. This practice isn't unheard of; Coptic is used exclusively as a religious language, and therefore its script is only seen in religious texts. This script is written entirely in majuscule to denote importance and each character is treated like an individual, calligraphic entity, though it is hopefully obvious which character is which to someone versed in simple Anampha. There are also no ligatures, meaning there are no contractions, so "it's" is written "it is". The example is a mock wedding announcement for good friends of mine who are married in real life, and hopefully they'll find the inclusion amusing. Because we don't live at Hogwarts the use of this in the real world is pretty limited, but hopefully I'll get two gravestones made so one of them is written like this.

After all this excitement and back-patting, a couple of horrible realizations came to me. Like most other phonetic scripts I made different symbols for "s" and "z", and in writing words that ended in "s" I used both the symbols based on the sounds that people actually speak as opposed to the one they write. Then it hit me: I'm using two different symbols to mean the same thing. We say two different things to mean the same grammatical device. But if I use two symbols...it...but then there's how we say different words the same that are written differently...and...I...grkh!

...

After regaining consciousness I could assess how much of a real problem this is, not just with Anampha but with all phonetic alphabets. Grammar and speech frequently don't create one-to-one correlations, and the use of "s" and "z" to represent the written "s" at the end of a word for plurals is a perfect example. In writing it's simple: we know exactly what sticking an "s" at the end of a word means. In speech, however, we alternate "s" and "z" sounds to deal with which sound came before it, something we're able to do no problem in practice because we know the theory behind it. Another example of bending the rules of grammar to fit speech patterns is the pronunciation of "-ed" for past tense verbs. Most of the time we just pronounce it as "d" but sometimes we say "ed", and that can vary depending on your region and breeding. For example, I learned to say "striped" as "straip-ed" but there's no good reason for me to say it like that rather than "straipd". Poetry often differentiates between these pronunciations to fit rhyming schemes, marking the annunciated "e" in "-ed" with a grave accent. Having to use diacritics is exactly the sort of thing that creating a phonetic alphabet is done to avoid, so by fixing that problem we've run into new ones. It isn't just fundamental grammar that the alphabet sometimes leaves in the cold, but also the internal logic of the language itself. One of the frequent arguments against spelling reform is that by changing how words are spelled the history of the word is obscured. Written English is lousy with fingerprints from old influences, such as tons of borrowed words from Romance languages and old reform attempts, and some would argue that covering that up with further reforms will make speakers and writers forget the language's heritage and the populace would be poorer for it. More importantly, spelling reform can often obscure etymology and word construction. Say what you will about how overstuffed some of our words can look, but you can frequently suss out where a word came from and how it was invented just by looking at it. The deeper you dip into etymology the more meaningful words become, and sometimes learning the original use of words based on etymology can uncover real poetry and add a new dimension to reading. English speakers gave up pronouncing words based on their theoretical structure a good long while ago, so reforming spelling based solely on sound would trample across these hidden histories. There's a temptation to calling these speech changes the result of laziness but that assessment isn't really fair when we took them as normal when first learning to speak and haven't done a damn thing to correct our own speech.

Are spelling reformers allowed to mess with these things? In some ways we're messing around on sacred ground, scrubbing out parts of our cultural heritage and filling them in with new stuff to fit our eccentric desires. Sure, we always do it for the betterment of humankind, but what if we're not expertly reshaping our script to make a better written future and instead are committing the linguistic equivalent of the time Mr. Bean accidentally wiped out the face of Whistler's Mother and tried correcting it in pencil? And more importantly, why bother? After all the work I put into creating Anampha, testing it, revising it and showing it to others, there was no point in which I thought anybody but myself would actually use the blasted thing, and not just because I'm a speck on a speck on a booger on a piece of gum on the bottom of a shoe in the grand scheme of things. It comes back to that old phrase: "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." Even if the non-broke thing is, in fact, broken, it's just "ain't" enough for us to grow up using it and lodge it so deeply in our muscle memory that no amount of logic and futurist optimism will get us to switch. How many different techniques have arisen to stop hiccups over the years that actually work, and how many times have you switched your method in the face of new info? I've been holding my diaphragm and sipping water for years but I've heard from reputable sources that swallowing a spoonful of dry sugar also works; I've also heard that the nerve that is overacting to create hiccups is the vagus nerve and that toying with it, specifically by inserting a finger into your anus and working it around, will stop hiccups dead in their tracks - that doesn't mean that I've adopted either of those techniques, and even though holding my breath doesn't work that well I'm not about to start fingering myself in public for the sake of taming my diaphragm. And it's fine. It's absolutely fine to stick with a less-than-perfect solution to a problem as long as it doesn't create problems longterm or on a large scale. No matter how much cheerleading I can do for Anampha the majority of the population will see it as nothing more than an unnecessary finger in the butt.

Is there much of a future for Anampha? Heck if I know. My little project was for fun, not profit, and success wasn't even the deciding factor as to whether or not I was going to write this article. I'll probably pull it out every now and then for yucks but I don't see myself writing professional emails in it any time soon. There will be more phonetic alphabets in the future from hobbyists and nutters like myself of varying levels of success, and that's great - conlangs and artlangs are a fascinating enthusiast field and should continue to see as much development as we'll allow. As much as I cringe at stuff like Ewellic I applaud small presses like Evertype for putting out editions of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in the script just so the option is available to us. In a world of near infinite archival space in digital form we shouldn't have to pick and choose which scripts to save and if nothing else each new script is another piece of the puzzle that is written English, another case either for or against spelling reform, and to be a good scientist one has to realize that there's no piece of evidence that's inherently not worth assessing. Language is an art as well as a science, and scripts like Deseret, Shavian and even Unifon are artistic statements worthy of discussion and admiration, and I'm happy even if Anampha is just a miniscule addition to the ranks of speculative attempts at a better written English.

But seriously, fuck Ewellic.

~PNK

1.) Easy to write

2.) Internal logic

3.) Internal distinctiveness

Hopefully these rules are simple but comprehensive, making sure that you don't have something that's simultaneously confusing and difficult to write, such as Barton or Ewellic. The elegance of Shavian was too tempting to ignore, obviously, so I'd need to keep some of the internal logic, such as having sounds that are clearly related, such as "ch" and "j", have similar shapes, and the fact that nearly every character can be written with a single stroke is also too excellent to ignore. However, I wanted to avoid some of the confusion with Shavian due to its simplicity. The "best in show" script for one that was less simple and less easy to write was Deseret, with its old-world, blocky personality, but that wasn't without its problems, such as a higher risk of carpal tunnel syndrome. With all of these things in mind, here's what I came up with:

Yes, I know this is initial draft is all a bit much to look at at first, but hear me out. My strategy was to take visual inspiration from the shape the mouth makes when forming each syllable, stylizing the shape as seen from a right-side profile and cross-sectioned to see just the front teeth, lips, roof and floor of the mouth and the tongue. For example, "t" and "d" are formed by placing the tip of the tongue at the intersection of the upper front teeth and the roof of the mouth, and so the basic shape is a diagonal line meeting a straight one above it on the right side, making a 45 degree angle. To differentiate the letters the "d" moves the lower line to meet the center of the upper line - this way neither one is too difficult to write and with practice it can be easily differentiated. Likewise "f" and "v" are formed by placing the lower lip close to the upper teeth to create a small aperture, and I had sensed that my lower lip was placed a bit higher for "v" than "f", so therefore the intersection of the two component lines was placed higher. Other visual relations included "n" and "m": "n" is formed much like "t" but because the sound was stopped rather than exploded I put a line dropping down from the diagonal to create a wall, and the "m" was that with an added tail at the bottom, like a cedille, to visually relate to how the lips close to create the "m" sound. In each case a miniscule and majuscule was created - those lines through each letter represent the height relationship between each letter, so the majuscule letters extend above the miniscule ones. There are a few graphemes that are similar to their Latin counterparts, such as the short "i" sound, and ones that are similar to different sounds in Latin, such as "u" which is identical to Latin's "o", but I kept true to my process and those symbols made the most sense to me both logically and aesthetically. I wanted to keep majuscule and miniscule rather than do away with it like Shavian and Ewellic as a nod to how European languages write with clear beginnings to sentences and also to preserve the official status of names and titles. I made a number of ligature characters not only for very common letter combinations, such as "st" and "sd", but also for all the basic articles and pronouns, as well as "and". I kept another element from Shavian in making ligature characters for each vowel ending in an "r" sound as those combinations are so liquid as to appear as one syllable and they are fairly common in English. I also couldn't resist borrowing an element of Deseret, namely the rule that you can use one character for "the", and in both Deseret and my alphabet it's the thick "th" character (as in "the").

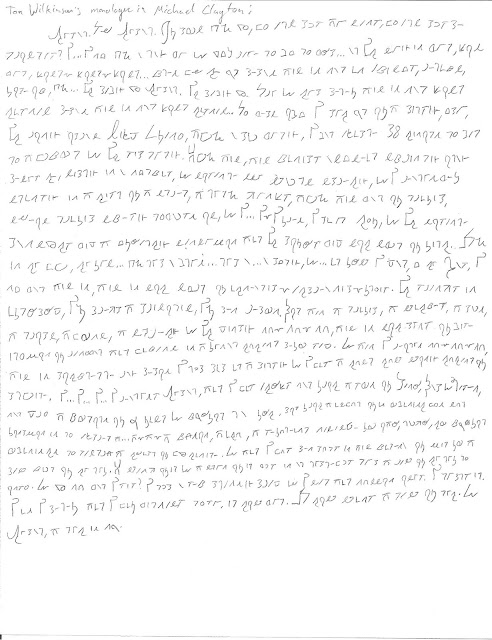

I believe the most important new inclusions, however, are two letter combinations that are very common in modern English but are conspicuously missing from all the alphabets I covered for these articles: the "x" and "qu" sounds. I can understand their disqualification from the others on the basis that, not only can a case be made for their being two syllables rather than one ("ks" and "kw"), but they are imported from Latin-based languages and aren't true to the spirit of English's Germanic roots. The latter argument is a bit hard to swallow these days, considering the Norman invasion was a thousand years ago and we've been using these sounds ever since then with no problem, but the first one merits discussion. Yes, these sounds are both combination sounds, but I have a number of ligatures already made and there's no reason not to make two more if the price is right. For "qu" I made a ligature of "k" and "w" with "w" on the left, making a kind of speech bubble character, and for "x" I created a new character entirely. With both miniscule and majuscule forms as well as ligatures the alphabet contains over 100 characters, far more than any of the other scripts, but in doing this almost every syllable and fundamental combination in written English should be covered with a single grapheme. I ended up calling the script (for now) Anampha, after "ANglo-AMerican alPHAbet", as I'm under no illusions that it would work for any other language; in the legend you can see its representation in the alphabet. In keeping things simple and easy to write a few of the characters ended up looking similar, but in testing I was able to keep them all straight with some practice. Here's a longish example, using Tom Wilkinson's big monologue at the beginning of Michael Clayton:

Obviously some small revisions were done to the original alphabet during and after this, such as removing the bottom line of "o" and the bottom connector of "p", things that made writing those letters unnecessarily irritating, but somethings I was very pleased with, especially the "ur" symbol, a sound that shows up a LOT in English. I also quite like the capital "ai" symbol for both the letter and article, giving a prominence and grace to the beginnings of a number of statements in this example. One problem that I still haven't worked out is how to represent hyphens, as "ee" is represented with an identical symbol in my alphabet. As the symbol is now, a hyphen with an angular dip in it, it's difficult to write accurately and ended up looking like a mistake most of the time. There are a few symbols which are still easy to confuse especially if hand-written, such as "ei" which is plainly an "ai" that got sat on - that grapheme is still tricky to write even after having written a substantial amount of material in the Anampha. As you can see my own handwriting standards got the better of me occasionally, such as the drunken sense of line and letter spacing that ended up confusing me when reading these passages after the fact - these issues didn't exactly clear up after more writing, though as my assurance with the characters improved the spacing did start to resemble the words I was trying to write. I managed to get out a particularly long passage, an entire short story by Lord Dunsany, a legend in the world of fantasy literature, called "The Hurricane". "The Hurricane" is actually one of my favorite stories, the witnessing of a Hurricane speaking with an Earthquake, and you can see the full text here. This is what it looks like in Anampha:

I'll leave that last line untranslated for those who like codes and Lovecraft references. This was written before a couple final touches were made to the script but in essence it shows everything I was going for with Anampha: elegance, distinction and ease of writing, all cutting down the number of characters needed by roughly a third and clearing up inconsistencies. In my excitement I came up with another idea, this one a bit more florid than the last:

These cast-off bits of wrought iron are the "ceremonial" version of Anampha. If used in a more fantastical setting than the real world, such as a fantasy novel, the story's interior world could use a script exclusively for religious texts or government announcements, hence the "ceremonial" designator. This practice isn't unheard of; Coptic is used exclusively as a religious language, and therefore its script is only seen in religious texts. This script is written entirely in majuscule to denote importance and each character is treated like an individual, calligraphic entity, though it is hopefully obvious which character is which to someone versed in simple Anampha. There are also no ligatures, meaning there are no contractions, so "it's" is written "it is". The example is a mock wedding announcement for good friends of mine who are married in real life, and hopefully they'll find the inclusion amusing. Because we don't live at Hogwarts the use of this in the real world is pretty limited, but hopefully I'll get two gravestones made so one of them is written like this.

After all this excitement and back-patting, a couple of horrible realizations came to me. Like most other phonetic scripts I made different symbols for "s" and "z", and in writing words that ended in "s" I used both the symbols based on the sounds that people actually speak as opposed to the one they write. Then it hit me: I'm using two different symbols to mean the same thing. We say two different things to mean the same grammatical device. But if I use two symbols...it...but then there's how we say different words the same that are written differently...and...I...grkh!

...

After regaining consciousness I could assess how much of a real problem this is, not just with Anampha but with all phonetic alphabets. Grammar and speech frequently don't create one-to-one correlations, and the use of "s" and "z" to represent the written "s" at the end of a word for plurals is a perfect example. In writing it's simple: we know exactly what sticking an "s" at the end of a word means. In speech, however, we alternate "s" and "z" sounds to deal with which sound came before it, something we're able to do no problem in practice because we know the theory behind it. Another example of bending the rules of grammar to fit speech patterns is the pronunciation of "-ed" for past tense verbs. Most of the time we just pronounce it as "d" but sometimes we say "ed", and that can vary depending on your region and breeding. For example, I learned to say "striped" as "straip-ed" but there's no good reason for me to say it like that rather than "straipd". Poetry often differentiates between these pronunciations to fit rhyming schemes, marking the annunciated "e" in "-ed" with a grave accent. Having to use diacritics is exactly the sort of thing that creating a phonetic alphabet is done to avoid, so by fixing that problem we've run into new ones. It isn't just fundamental grammar that the alphabet sometimes leaves in the cold, but also the internal logic of the language itself. One of the frequent arguments against spelling reform is that by changing how words are spelled the history of the word is obscured. Written English is lousy with fingerprints from old influences, such as tons of borrowed words from Romance languages and old reform attempts, and some would argue that covering that up with further reforms will make speakers and writers forget the language's heritage and the populace would be poorer for it. More importantly, spelling reform can often obscure etymology and word construction. Say what you will about how overstuffed some of our words can look, but you can frequently suss out where a word came from and how it was invented just by looking at it. The deeper you dip into etymology the more meaningful words become, and sometimes learning the original use of words based on etymology can uncover real poetry and add a new dimension to reading. English speakers gave up pronouncing words based on their theoretical structure a good long while ago, so reforming spelling based solely on sound would trample across these hidden histories. There's a temptation to calling these speech changes the result of laziness but that assessment isn't really fair when we took them as normal when first learning to speak and haven't done a damn thing to correct our own speech.

Are spelling reformers allowed to mess with these things? In some ways we're messing around on sacred ground, scrubbing out parts of our cultural heritage and filling them in with new stuff to fit our eccentric desires. Sure, we always do it for the betterment of humankind, but what if we're not expertly reshaping our script to make a better written future and instead are committing the linguistic equivalent of the time Mr. Bean accidentally wiped out the face of Whistler's Mother and tried correcting it in pencil? And more importantly, why bother? After all the work I put into creating Anampha, testing it, revising it and showing it to others, there was no point in which I thought anybody but myself would actually use the blasted thing, and not just because I'm a speck on a speck on a booger on a piece of gum on the bottom of a shoe in the grand scheme of things. It comes back to that old phrase: "If it ain't broke, don't fix it." Even if the non-broke thing is, in fact, broken, it's just "ain't" enough for us to grow up using it and lodge it so deeply in our muscle memory that no amount of logic and futurist optimism will get us to switch. How many different techniques have arisen to stop hiccups over the years that actually work, and how many times have you switched your method in the face of new info? I've been holding my diaphragm and sipping water for years but I've heard from reputable sources that swallowing a spoonful of dry sugar also works; I've also heard that the nerve that is overacting to create hiccups is the vagus nerve and that toying with it, specifically by inserting a finger into your anus and working it around, will stop hiccups dead in their tracks - that doesn't mean that I've adopted either of those techniques, and even though holding my breath doesn't work that well I'm not about to start fingering myself in public for the sake of taming my diaphragm. And it's fine. It's absolutely fine to stick with a less-than-perfect solution to a problem as long as it doesn't create problems longterm or on a large scale. No matter how much cheerleading I can do for Anampha the majority of the population will see it as nothing more than an unnecessary finger in the butt.

Is there much of a future for Anampha? Heck if I know. My little project was for fun, not profit, and success wasn't even the deciding factor as to whether or not I was going to write this article. I'll probably pull it out every now and then for yucks but I don't see myself writing professional emails in it any time soon. There will be more phonetic alphabets in the future from hobbyists and nutters like myself of varying levels of success, and that's great - conlangs and artlangs are a fascinating enthusiast field and should continue to see as much development as we'll allow. As much as I cringe at stuff like Ewellic I applaud small presses like Evertype for putting out editions of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in the script just so the option is available to us. In a world of near infinite archival space in digital form we shouldn't have to pick and choose which scripts to save and if nothing else each new script is another piece of the puzzle that is written English, another case either for or against spelling reform, and to be a good scientist one has to realize that there's no piece of evidence that's inherently not worth assessing. Language is an art as well as a science, and scripts like Deseret, Shavian and even Unifon are artistic statements worthy of discussion and admiration, and I'm happy even if Anampha is just a miniscule addition to the ranks of speculative attempts at a better written English.

But seriously, fuck Ewellic.

~PNK